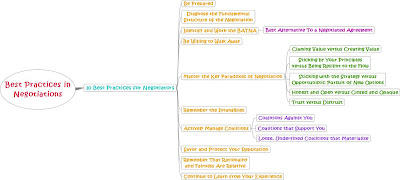

Negotiation is an integral part of daily life and the opportunities to negotiate surround us. In this final chapter we reflect on negotiation at a broad level by providing 10 best practices for negotiators who wish to continue to improve their negotiation skills.

10 Best Practices for Negotiators

1. Be Prepared

Preparation does not have to be a time-consuming or arduous activity, but it should be right at the top of the best practices list of every negotiator.

2. Diagnose the Fundamental Structure of the Negotiation

Negotiators should make a conscious decision about whether they are facing a fundamentally distributive negotiation, an integrative negotiation, or a blend of the two, and choose their strategies and tactics accordingly. In these situations, money and opportunity are often left on the table.

3. Identify and Work the BATNA

One of the most important sources of power in a negotiation is the alternatives available to a negotiator if an agreement is not reached. One alternative, the best alternative to a negotiated agreement (BATNA), is especially important because this is the option that likely will be chosen should an agreement not be reached.

4. Be Willing to Walk Away

Strong negotiators remember this and are willing to walk away from a negotiation when no agreement is better than a poor agreement or when the process is so offensive that the deal isn’t worth the work.

5. Master the Key Paradoxes of Negotiation

Strong negotiators know how to manage these situations.

- Claiming Value versus Creating Value

- Sticking by Your Principles versus Being Resilient to the Flow

- Sticking with the Strategy versus Opportunistic Pursuit of New Options

- Honest and Open versus Closed and Opaque

- Trust versus Distrust

6. Remember the Intangibles

It is important that negotiators remember the intangible factors while negotiating and remain aware of their potential effects. Intangibles frequently effect negotiation in a negative way, and they often operate out of the negotiator’s awareness.

7. Actively Manage Coalitions

Coalitions can have very significant effects on the negotiation process and outcome. Three types of coalitions and their potential effects: 1) coalitions against you; 2) coalitions that support you; and 3) loose, undefined coalitions that may materialize either for or against you.

8. Savor and Protect Your Reputation

Reputations are like eggs – fragile, important to build, easy to break, and very hard to rebuild once broken. Reputations travel fast, and people often know more about you than you think that they do.

9. Remember That Rationality and Fairness Are Relative

Negotiators are often in the position to collectively define what is right or fair as a part of the negotiation process. Be prepared to negotiate these principles as strongly as you prepare for a discussion of the issues.

10. Continue to Learn from Your Experience

Negotiation epitomizes lifelong learning. Three steps to process: Plan a personal reflection time after each negotiation, Periodically take a lesson from a trainer or coach, and Keep a personal diary on strengths and weaknesses and develop a plan to work on weaknesses.